Not surprisingly, an exploration of archetypes in human society is similar to the idea that myths are foundational to both personal and group identity. Joseph Campbell has aptly demonstrated the ongoing power of primary myths (defining narratives) throughout human history. For my purposes, I just want to highlight a particular aspect of myth and relate it to the role of Jesus, and this is what Campbell called “the mono-myth” or “the hero’s journey.” Heroes are persons, alive or dead, real or imaginary, who possess characteristics that are highly prized in a culture and thus serve as models for behavior.

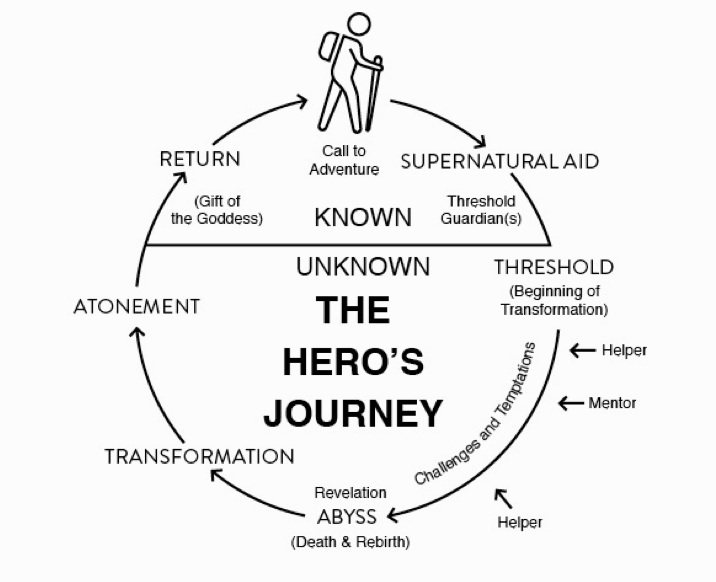

According to Campbell and others (e.g., C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, C. Vogler), the hero’s journey has a definite pattern and mythic structure. These are easily discernable in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and in Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia, but actually form the structure of all myth and great story.1 Once you know what to look for, the pattern is universally evident. In fact, according to Campbell, the hero’s journey can be broken down into three sections with various sub-stages in each section. These are: Quest (or Departure), Ordeal, and Return. The Quest includes the hero being summonsed and sent, venturing forth on the journey. The Ordeal comprises the hero’s initiation, wounding, battles, setbacks, and various adventures along the way, and the Return encompasses the hero’s return home with the elixir of life—the special knowledge and powers acquired on the journey. Campbell described it this way:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

This story is as ancient as time itself, and it carries huge significance for every culture everywhere. If you think about this in terms of your favorite action movie for instance, you will be able to discern all the stages in the hero’s journey, from The Bourne Identity to The Matrix and anything in-between. In many ways, myth is the Story behind and within all stories. And it permeates history, religion, and culture. As Balthasar said:

Divine grace … is secretly at work in the whole sphere of history, and thus all myths, philosophies, and poetic creations are innately capable of housing within themselves an intimation of divine glory.

Paul, particularly in his apostolic-missionary function, is fully attuned to the underlying religious significance of ancient pagan religious myth as a rich metaphor for Christ’s death and resurrection. For instance, in Acts 17:16–34 (esp. v. 23) he is in all likelihood referring to some myth of a dying and rising God, probably the god Ceres. Ceres (from where we get our word “cereal”) was the Corn King that was believed to die and rise again with every new season. Paul uses the internal logic of the narrative to make a direct appeal for the parallel in the Jesus story. This is because of the abiding value of monomyth as a metaphor for the gospel. Listen to the master storyteller C.S. Lewis here:

In theology as in science, myth supplies not answers but an experience of a larger existence than we can know cognitively. Such an experience touches depths the intellect cannot reach and conveys, to children and adults alike, the sense that this is not just true, but Truth.

J.R.R. Tolkien once suggested to C.S. Lewis that the gospel sounded like a reframing of the Corn King myth because Christ was a myth that had become fact.7 Christ lived (and so fulfilled) the myth that was already hidden in culture. Or, as Lewis scholar Louis Marcos says:

Perhaps the reason that every ancient culture yearned for a god to come to earth, to die, and to rise again was because the Creator who made all the nations placed in every person a desire for this very thing.

And, if that is the case, then does it not make sense that when God enacted his salvation in the world through Jesus, he did it in a way that deeply resonated with the desire that he put in all people?

Once we have acknowledged this archetypal pattern of myth, it’s not hard to see the hero’s journey pattern fitting the characteristic pattern of Jesus’ story—Jesus is sent on a mission, embodying the APEST identities; Jesus labors and suffers for the cause and gains a devoted following; Jesus overcomes and achieves victory; Jesus bestows the blessing of the fivefold (see Figure 5.2). In a word, Jesus is our true “hero” and serves as the primary Christian prototype … the heroic form, perfected man in whose image we are being remade (2 Corinthians 3:18).